Metaphysics » Lecture 6

Two ideas about how to understand ‘not confined to an instant’:

The two main accounts of persistence start from these ideas:

Let us say that something persists iff, somehow or other, it exists at various times; this is the neutral word. Something perdures iff it persists by having different temporal parts, or stages, at different times, though no one part of it is wholly present at more than one time; whereas it endures iff it persists by being wholly present at more than one time. (Lewis 1986a: 202)

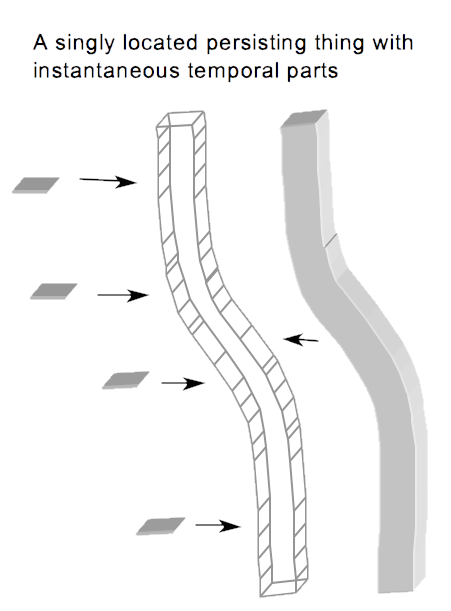

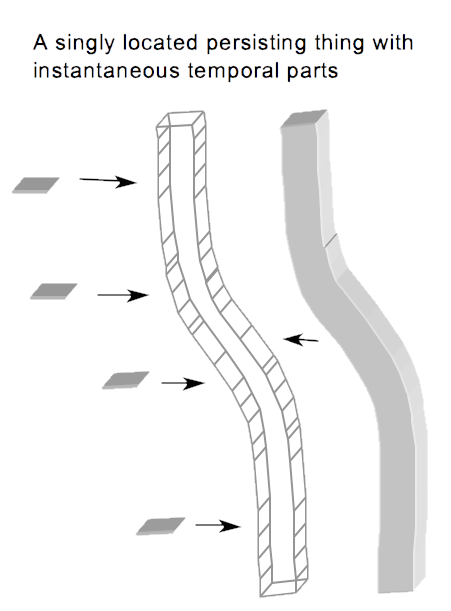

Perdurance says that extending through time (i.e., persisting) is like extending across space; objects do that by having different parts at each place.

Perdurance – otherwise known as four-dimensionalism (though this is misleading, since it is a view about things, not space and time – see Parsons (2000)) – is widely defended (Smart 1963; Hawley 2001; Balashov 2010).

It is the natural approach to the persistence of events: a war has a duration, and battles and campaigns, etc., are parts of it that occupy briefer durations.

This analogy with events helps us understand perdurance:

Think of your life as a long story. … Like all stories, this story has parts. We can distinguish the part of the story concerning childhood from the part concerning adulthood. Given enough details, there will be parts concerning individual days, minutes, or even instants.

According to the ‘four-dimensional’ conception of persons (and all other objects that persist over time), persons are a lot like their stories. Just as my story has a part for my childhood, so I have a part consisting just of my childhood. Just as my story has a part describing just this instant, so I have a part that is me-at-this-very-instant (Sider 2001: 1)

Obviously, this is exactly Lewis’ view of persons as aggregates of distinct person stages (1976: 59) from last time.

Objection. I understand the illustration, which makes spatial and temporal parts look analogous (just rotate the diagram 90°). But I think there are disanalogies too: time just is different from space, and we cannot just assume that what appears to make analogical sense really is conceptually coherent. I understand the notion of a part; but that is a spatial notion (my parts are those things I contain; my hand, for example, which persists just as much as I do). I cannot understand the atemporal relation of parthood needed for temporal parts to make sense.

Almost everyone believes that things have spatial parts: my hand is part of me, maybe cells are part of it (and, in turn, of me), molecules part of cells, and so on down to the smallest sub-atomic particles (if there are any – or maybe divisibility goes on forever).

These proper parts are smaller than me, but overlap me: ‘they are “cut out of” me along a spatial dimension’ (Sider 2001: 2).

They may not be separable, but they are still parts:

Talk of cutting and slicing must be taken with a grain of salt: the parts are there whether or not they are physically separated from the whole. (Sider 2001: 2)

The perdurantist argues that, exactly analogously, there are temporal (proper) parts: slices or segments of me along a temporal dimension.

To understand this, let’s start with a four-dimensional manifold of space and time: a B-theoretic block universe.

Material things have locations in this spacetime.

Persisting things have locations that are spacetime regions, extended in space and time.

A block universe picture permits us to understand four-dimensional objects in just the same sort of way we understand three-dimensional objects:

just as we might talk about the distance between two points along a line in space, we can also talk about the distance between two points in time. This allows us to understand the notion of temporal boundaries as analogous to that of spatial boundaries. Furthermore, there is an analogy with respect to the part-whole relationship. Just as a spatial part fills up a sub-region of the space occupied by the whole, a temporal part fills up a sub-region of the time occupied by the whole. (Heller 1984: 325)

Once we understand four-dimensional objects, we can understand their parts:

A four dimensional object is the material content of a filled region of spacetime. A spatiotemporal part of such an object is the material content of a sub-region of the spacetime occupied by the whole. For instance, consider a particular object \(O\) and the region \(R\) of spacetime that \(O\) fills. A spatiotemporal part of \(O\) is the material content of a sub-region of \(R\). A spatiotemporal part, as long as it has greater than zero extent along every dimension, is itself a four dimensional physical object. A spatiotemporal part is not a set or a process or a way something is at a place and time. It, like the object it is part of, is a hunk of matter. (Heller 1984: 326)

We believe in a plenitude of subregions of a given region: a region is made out of points, and we might well believe, there is a region – perhaps disconnected or scattered, perhaps very weirdly shaped – corresponding to any subcollection of those points.

Two questions arise, over the truth of two principles.

Heller is sympathetic to DAUP and the Liberal view, but it is perfectly consistent with the perdurantist picture that only some subregions of \(O\)’s location are occupied by a part of \(O\) (Heller 1984: 327).

What is a temporal part? It is a spatiotemporal part which is smaller than the whole object along the temporal dimension, but only that dimension.

It is as large as the object spatially at the times at which both exist; but it is shorter lived, perhaps radically so.

a temporal part of \(O\) is the material content of a temporal sub-region of \(R\). ‘Temporal sub-region of \(R\)’ means spatiotemporal sub-region that shares all of \(R\)’s spatial boundaries within that sub-region’s temporal boundaries. A temporal part of me which exists from my fifth birthday to my sixth is the same spatial size I am from age five to age six. (Heller 1984: 328)

[P]erdurantism has been recommended on the grounds that: (i) it solves several of the puzzles that raise the problem of material constitution; (ii) it is (at least) suggested by the special theory of relativity…; (iii) it is the only view that makes sense out of the possibility of intrinsic change; (iv) it is the only view consistent with the doctrine of Humean supervenience; and (v) it makes better sense than its competitor out of the possibility of fission. These are the primary and most powerful claims that have been made on behalf of perdurantism. (Rea 1998: 225)

Humean Supervenience is the view that there can’t be distinct possible worlds that are exactly alike in ‘the distribution of local qualities and their causal relations’ (Lewis 1976: 77; see also Lewis 1986b: ix–xvii).

Lewis (1976: 76–77) argues that if Humean Supervenience is true, then things are made of temporal parts. The general argument form is something like this:

Non-perdurantists will likely get off at step 1: why think instantaneous things are just like the stages of persisting things?

Suppose I put a new 7-inch taper on the table before dinner and light it. At the end of dinner when I blow it out, it is only 5 inches long. We know that a single object cannot have incompatible properties, and being 7 inches long and being 5 inches long are incompatible. So instead of there being one candle that was on the table before dinner and also after, there must be two distinct candles: the 7-inch taper and the 5-inch taper. But of course the candle didn’t shrink instantaneously from 7 inches long to 5 inches long: during the soup course it was 6.5 inches long; during the main course it was 6 inches long; during dessert it was 5.5 inches long. Following the thought that no object can have incompatible lengths, we must conclude, it seems, that during dinner there were several (actually many more than just several) candles on the table in succession. (Haslanger 2003: 315–16)

- Persistence condition

- Objects, such as a candle, persist through change.

- Incompatibility condition

- The properties involved in a change are incompatible.

- Law of non-contradiction

- Nothing can have incompatible properties, i.e., nothing can be both \(\Phi\) and not-\(\Phi\).

- Identity condition

- If an object persists through a change, then the object existing before the change is one and the same object as the one existing after the change: that is, the original object continues to exist through the change.

- Proper subject condition

- The object undergoing the change is itself the proper subject of the properties involved in the change; for example, the persisting candle is itself the proper subject of the incompatible properties. (Haslanger 2003: 316–17)

A person’s journey through time is like a road’s journey through space. The dimension along which a road travels is like time; a perpendicular axis across the road is like space. Parts cut the long way – lanes – are like spatial parts, whereas parts cut crosswise are like temporal parts. US Route 1 extends from Maine to Florida by having subsections in the various regions along its path. The bit located in Philadelphia is a mere part of the road, just as it is only a mere part of me that is contained in 1998.

A road changes from one place to another by having dissimilar sub-sections. Route 1 changes from bumpy to smooth by having distinct bumpy and smooth subsections. On the four-dimensional picture, change over time is analogous: I change from sitting to standing by having a temporal part that sits and a later temporal part that stands. (Sider 2001: 2)

It is a disadvantage of the perdurance account that it sacrifices the proper subject condition. How? Consider again the candle’s change from straight to bent. On the perdurance view, the proper subject of straightness is the early candle-stage; the proper subject of bentness is the later candle-stage. The candle composed of these parts is not strictly speaking both straight and bent (otherwise we would be left again with a contradiction), but is only indirectly or derivatively straight and bent by virtue of having parts that are. (Haslanger 2003: 331)

A sentence or statement or proposition that ascribes intrinsic properties to something is entirely about that thing; whereas an ascription of extrinsic properties to something is not entirely about that thing, though it may well be about some larger whole which includes that thing as part. A thing has its intrinsic properties in virtue of the way that thing itself, and nothing else, is. Not so for extrinsic properties, though a thing may well have these in virtue of the way some larger whole is … If something has an intrinsic property, then so does any perfect duplicate of that thing; whereas duplicates situated in different surroundings will differ in their extrinsic properties (Lewis 1983: 111–12)

[Maybe] shapes are not genuine intrinsic properties. They are disguised relations, which an enduring thing may bear to times. One and the same enduring thing may bear the bent-shape relation to some times, and the straight-shape relation to others. In itself, considered apart from its relations to other things, it has no shape at all. And likewise for all other seeming temporary intrinsics… The solution to the problem of temporary intrinsics is that there aren’t any temporary intrinsics. This is simply incredible, if we are speaking of the persistence of ordinary things.… If we know what shape is, we know that it is a property, not a relation. (Lewis 1986a: 204)

Must an endurantist reject intrinsic properties?

Perhaps they can redefine intrinsic, so that relations to times can count as intrinsic in the relevant sense (and hence (5) is false):

A relation to a time \(R\) is intrinsic iff for all \(x\) and \(y\), and any times \(t_{1}\) and \(t_{2}\), if \(x\) at \(t_{1}\) is a duplicate\(_{\text{E}}\) of \(y\) at \(t_{2}\), then either \(R(x, t_{1})\) and \(R(y, t_{2})\), or \(\neg R(x, t_{1})\) and \(\neg R(y, t_{2})\). (Eddon 2010: 608)

But this move, and others like it, still runs afoul of the intuition:

The endurantist may contrive a sense in which her ephemera are intrinsic and monadic, but nonetheless these properties seem unacceptably relational. (Eddon 2010: 608–9)

Next time we will consider some more sophisticated B-endurantist responses to the problem of temporary intrinsics.

I am willing to grant Lewis’s assertion that, once someone admits that I have more properties than just those I have now, she must choose between [treating properties as relations to times, or perdurantism]. What I want to question instead is the very first move: Why suppose that I must have more than just the properties I have now? (Zimmerman 1998: 207–8)

the presentist could not very well regard all the fundamental truth-bearers as eternally true, corresponding to tenseless statements. For, she says, one of the truths is that wholly future things, like my first grandchild, do not exist – and such truths had better be susceptible to change (Zimmerman 1998: 211–12)

But there is still a question about how it is, abstracted from its changing history, i.e., abstracted from its variation from time to time. We cannot describe the enduring object in these terms as simply bent or straight; so it could only be shapeless.…

although a description of the enduring object which abstracts from its changing history does not include a particular shape as part of that description…, such a description is incomplete; most importantly, it doesn’t include all of the intrinsic properties of the object because some of the intrinsic properties of the object are had at some times and not at others. … The endurance theorist denies that the description which characterizes the object ‘timelessly’ is the description which captures all of the intrinsic properties of the object. The enduring object is bent and then straight; it is not a shapeless blob. (Haslanger 1989: 124)

Second solution: the only intrinsic properties of a thing are those it has at the present moment. Other times are like false stories; they are abstract representations, composed out of the materials of the present, which represent or misrepresent the way things are. When something has different intrinsic properties according to one of these ersatz other times, that does not mean that it, or any part of it, or anything else, just has them – no more so than when a man is crooked according to the Times, or honest according to the News. This is a solution that rejects endurance; because it rejects persistence altogether.… In saying that there are no other times… it goes against what we all believe. No man, unless it be at the moment of his execution, believes that he has no future; still less does anyone believe that he has no past. (Lewis 1986a: 204)

Lewis thinks this is ‘obviously true’:

Does this commit me to the existence of times other than the present? Well, when I ask myself whether I think that my childhood exists, …, the answer comes back a resounding No. Is it just that I feel that past and future things and events can be regarded as nonexistent because they are ‘temporally far’ from me? I think not – the past is no more, and the future is not yet, in the strictest sense. And so those who share this judgment begin the work of philosophical paraphrase, trying to find plausible construals of statements like … (PC) that capture what is meant but do not involve direct reference to nonpresent times, individuals, and events (Zimmerman 1998: 214–15)

So, for instance, (PC) can be taken as a tenseless statement expressing a disjunction of tensed propositions: Either I was bent and would become or had previously been straight, or I was straight and would become or had previously been bent, or I will be bent and will have been or be about to become straight, or I will be straight and will have been or be about to become bent. Surely this tensed disjunction is true if (PC) is true; furthermore, it contains no mention of anything like a nonpresent time. So, given the presentist’s desire to avoid ontological commitment to nonpresent times, this tensed statement provides a perfectly sensible paraphrase of my conviction that I can persist through change of shape (Zimmerman 1998: 215)

The large-scale project of paraphrasing truths ostensibly about nonpresent times and things is as complex and difficult as the counterpart project concerning nonactuals. Ways must be found to capture all truths about past and future things without the appearance of ontological commitment to such things (Zimmerman 1998: 215)

How might the four-dimensional conception be supported? One way is by appeal to its utility in defusing certain classic puzzle cases about identity over time. … From [considering] traditional puzzles about identity over time, a powerful case emerges for postulating a four-dimensional world of temporal stages. If we believe in perdurantism, we can dissolve these and other puzzle cases; if we do not, we are left mired in contradiction and paradox. (Sider 2001: 4–10)

Suppose that on Monday an artist obtains a lump of clay, and on Tuesday forms a statue using that clay. It is natural to say that the artist has created something…. After the act of creation, let us name the lump of clay (which is now in statue form) Lump; and let us name the statue Statue. Lump and Statue seem to be one and the same object. But if they are to be identical, Leibniz’s Law requires them to share all of their properties. Lump and Statue do share many properties: they have the same mass, the same shape, the same location, and are made up of the same subatomic particles. But if we turn our attention to historical properties, we find differences. Since the statue was created on Tuesday, it did not exist on Monday, but the lump did exist on Monday. Therefore, Statue ≠ Lump, since only Lump has the property existing on Monday. But how can this be? (Sider 2001: 5)

One nice ramification of these considerations is that an object and a proper part of that object do not, strictly speaking, exist in the same space at the same time. An object is not coincident with any of its proper parts. Intuitively, the problem with coincident entities is that of overcrowding. There is just not enough room for them. But an object and a part of that object do not compete for room. There is a certain spatiotemporal region exactly occupied by the part; the whole object is not in that region. There is only as much of the object there as will fit – namely, the part. (Heller 1984: 329)

I make a clay statue of the infant Goliath in two pieces, one the part above the waist and the other the part below the waist. Once I finish the two halves, I stick them together, thereby bringing into existence simultaneously a new piece of clay and a new statue. A day later I smash the statue, thereby bringing to an end both statue and piece of clay. The statue and the piece of clay persisted during exactly the same period of time. (Gibbard 1976: 191)

Imagine replacing The Ship of Theseus’s planks one by one until all the original planks are gone, and christen the final ship ‘Replacement’. Since replacement of a single plank does not destroy a ship, we obtain a series of true identity statements… By the principle of the transitivity of identity …, The Ship of Theseus = Replacement. … But now imagine that each plank removed during this process was saved in a warehouse. After enough planks accumulated, we began assembling them into a new ship. … We now face a difficult question: which ship is the same ship as the original Ship of Theseus? We argued via the transitivity of identity that Replacement is The Ship of Theseus; but Planks also has a powerful claim since it contains all the original planks. Surely a ship could be transported over land by disassembly and subsequent reassembly; the case of The Ship of Theseus and Planks seems parallel. (Sider 2001: 6–7)

Perdurantists often accept this principle:

So there are such things as Planks and Replacement.

And there are even such things as arbitrary spacetime worms, including these two: (i) one that begins with the Ship of Theseus, and end in Planks, and has the scattered fusion of Planks’ planks as its temporal part at every time; and (ii) another that also begins with the Ship of Theseus, ends in Replacement, and has a ship in various stages of repair as its temporal part at every time.

Which really is the Ship of Theseus though?

Perhaps our concept of a ship does not emphasize sameness of planks, and applies to spacetime worms that continue in ship form even if they exchange planks. The replacement worm rather than the original planks worm would then count as a ship, and the correct answer to the question would be Replacement. …

On the other hand, perhaps it is a feature of our concept of a ship that ships must retain the same planks. The original planks worm, rather than the replacement worm, might then count as a ship. …

… the metaphysical puzzle has been dissolved. We have a perfectly clear metaphysical picture of what happens: the world contains spacetime worms corresponding to both answers to our question. The only remaining question is the merely conceptual one of which of these spacetime worms counts as a ship. (Sider 2001: 9–10)

This idea of a conceptual question might help with Goliath and Lumpl too.

Consider the idea of a counterpart:

Where some would say that you are in several worlds, in which you have somewhat different properties and somewhat different things happen to you, I prefer to say that you are in the actual world and no other, but you have counterparts in several other worlds. Your counterparts resemble you closely in content and context in important respects. They resemble you more closely than do the other things in their worlds. But they are not really you. For each of them is in his own world, and only you are here in the actual world. (Lewis 1968: 114)

According to counterpart theory, a modal claim like ‘Lumpl could survive being squashed’ is true iff there is some possible counterpart of Lumpl that is (in another possibility) squashed.

A counterpart ‘resembles you… in important respects’; but since similarity and importance are both context-sensitive notions, one and the same object can have multiple counterpart relations, depending on which of its features we emphasise (Sider 2001: 223).

Counterpart theory, plus context sensitivity, allows us to say that Lumpl could survive being squashed is true in context \(c\) (because Lumpl has a squished counterpart lump); that Goliath could survive being squashed is false in context \(c'\) (becuse Goliath lacks a squished counterpart statue); and Goliath = Lumpl:

By contrast with the space-time worms, statues and pieces of [clay] are not purely extensional entities. For while they are nothing over and above their parts according to four-dimensionalism, the salient counterpart relations depend on how we conceive of those parts, whether as a statue, a piece of [clay], or some other way. … that conception … determine[s] what we can truly say – what we may predicate – of the piece of [clay]. (Eagle 2007: 161)