Philosophy of Language » Lecture 5

The primary function of an assertion of a declarative sentence is to say something about how things are.

Since the world is how a sentence says it is iff that sentence is true, what a declarative sentence says must be capable of truth or falsity.

For an internalist, who thinks the meanings of individual words are concepts in a speaker’s head, it is natural to take the meaning of a sentence to be likewise a concept:

an internal mental structure arrived at in a compositional fashion from the meanings of the words in the sentence and their syntactic arrangement. (Elbourne 2011: 43)

Given the above, any concept which could be the meaning of a sentence must be one that applies to a scenario (or to ‘reality as whole’?) iff the sentence is true.

Consider the proposition sentences:

- John said something.

- What John said was true.

- Though what John said was true, it would have been false had things gone differently.

- What John said is what Mary believed.

… the proposition sentences seem to jointly entail:

- There is something that John said, and which was true, and which could have been false, and which Mary believed.

… If (5) is true, then there are things which are said and believed, which are the bearers of truth values and have modal properties like being possibly true. So if (5) is true, there are propositions. (Speaks 2014: 10–11)

… There is something they both believe is ambiguous. On [the orthodox] way of reading it, the sentence does indeed assert the existence of an object to which both [John] and [Mary] stand in the belief relation. An internalist will say that on that reading the sentence is simply false…. On another reading, the sentence … would be claiming … that [John]‘s belief and [Mary]’s belief are qualitatively identical. We can compare a sentence like There is something they both own. This could mean there is a particular concrete object of which [John] and [Mary] are joint owners; but alternatively it could mean that there is a kind of object such that [John] and [Mary] both own objects of that kind. To an assertion that [John] and [Mary]’s possessions are completely dissimilar, it would be possible to reply, ’No, there is something they both own—a house’. This would not necessarily imply that they own the same house. (Elbourne 2011: 45–46)

Let’s consider another example:

Is it possible to interpret the occurrence of it in this sentence as denoting something only qualitatively similar to the object of Harold’s belief?

I don’t believe so. It is parasitic upon that there is life on Venus.

Compare Elbourne’s parallel case:

There is no way to interpret this example except as saying that Harold and Fiona are joint owners; similarly with (6). But (6) is true: so there are abstract non-internalist propositions.

The referentialist offers a simple and elegant account of the attitudes:

The Relational Analysis can easily explain the validity of this and similar argument forms: the argument on the left has the logical form on the right. Harder for internalists to explain why the argument is good.

Charles believes everything Thomas says.

Thomas says that cats purr.

So, Charles believes that cats purr.

\(\forall x (\text{Thomas says that } x \to \text{Charles believes that }x)\).

Thomas says that \(p\).

So, Charles believes that \(p\).

What is the extension of a sentence? To what does a sentence ‘refer’?

Every declarative sentence concerned with the reference of its words is therefore to be regarded as a proper name, and its reference, if it has one, is either the True or the False. (Frege 1892: 29)

Given this, the intension of a sentence is a function from possible situations to truth values (because an intension in general is a function from possible situations to extensions).

But since there are only two truth values, the intension of a sentence is equivalently a set of possible situations: writing \(⟦S⟧\) for the intension of \(S\), \(⟦S⟧=\{w: S\text{ is true in }w\}\).

So an intension just is an unstructured proposition!

Everyone – internalists and all sorts of referentialists – offers a conception of a proposition on which a proposition determines an intension.

And so most formal semanticists accept that even if they aren’t exactly sentence meanings, intensions do a decent job at modelling interesting features of sentence meaning (Elbourne 2011: 46).

So we can start by adopting – for the sake of exploration – the suggestion that a proposition just is – or can be satisfactorily represented as – an unstructured proposition, or intension.

We’ll see how far we can get with the idea that the meaning of a sentence is given by the possible conditions under which it is true – its truth conditions.

We need not take this fully literally, though some very distinguished philosophers have:

a proposition is a set of possible worlds. A proposition is said to hold at a world, or to be true at a world. The proposition is the same thing as the property of being a world where that Proposition holds; and that is the same thing as the set of worlds where that proposition holds. A proposition holds at just those worlds that are members of it. (Lewis 1986: 53–54)

a proposition is a function from possible worlds into truth-values. (Stalnaker 1984: 2)

[T]he primary objects of attitudes are … alternative possible states of the world. When a person wants a proposition to be true, it is because he has a positive attitude towards certain concrete realizations of that proposition. Propositions … are simply ways of distinguishing between the elements of the relevant range of alternative possibilities – ways that are useful for characterizing and expressing an agent’s attitudes toward those possibilities. To understand a proposition – to know the content of a statement or thought – is to have the capacity to divide the relevant alternatives the right way. … To distinguish two propositions is to conceive of a possible situation in which one is true and the other false. (Stalnaker 1984: 4–5)

According to the conception of content that lies behind the possible worlds analysis of propositions and propositional attitudes, content requires contingency. To learn something, to acquire information, is to rule out possibilities. To understand the information conveyed in a communication is to know what possibilities would be excluded by its truth. (Stalnaker 1984: 85)

We’ve already mentioned ‘possible worlds’ a number of times – when characterising intensions, when thinking about Kripke’s notion of a rigid designator, etc.

But what are these things? Lewis offers the most radical, and yet most straightforward story:

When I profess realism about possible worlds, I mean to be taken literally. Possible worlds are what they are, and not some other thing. If asked what sort of thing they are, I cannot give the kind of reply my questioner probably expects: that is, a proposal to reduce possible worlds to something else.

I can only ask him to admit that he knows what sort of thing our actual world is, and then explain that possible worlds are more things of that sort, differing not in kind but only in what goes on at them. (Lewis 1973: 85; see also Lewis 1986)

I believe there are possible worlds other than the one we happen to inhabit. If an argument is wanted, it is this: It is uncontroversially true that things might have been otherwise than they are. I believe, and so do you, that things could have been different in countless ways. But what does this mean? Ordinary language permits the paraphrase: there are many ways things could have been besides the way that they actually are. On the face of it, this sentence is an existential quantification. It says that there exist many entities of a certain description, to wit, ‘ways things could have been’. I believe things could have been different in countless ways. I believe permissible paraphrases of what I believe; taking the paraphrase at its face value, I therefore believe in the existence of entities which might be called ‘ways things could have been’. I prefer to call them ‘possible worlds’. (Lewis 1973: 84)

An alternative account is this (Stalnaker 1976; Kripke 1980: 43–46): a possible world is a way that (actual) things might have been, but that isn’t a concrete thing (akin to ‘I and all my surroundings’) – it’s a property that I and all my surroundings might have had.

We start with the things we can actually talk about in our current language and we can make up some stories about those things in our language. If the story could have been true, then the way the story (falsely) says things are is a way things could have been, and is thus a possible world – a property that our world could have had, and which determines what would have been true if our world had turned out to have it.

This is a kind of realism: but we commit to abstract uninstantiated properties, not to a pluriverse of real talking donkeys, etc.

The way things are is a property or a state of the world, not the world itself. The statement that the world is the way it is is true in a sense, but not when read as an identity statement…. One could accept … that there really are many ways that things could have been … while denying that there exists anything else that is like the actual world. (Stalnaker 1976: 68)

The fact that something in a logical model is called a ‘world’ doesn’t mean that it is a concrete entity, like our universe, existing in a ‘pluriverse of alternate realities’. It is enough that it be something relative to which sentences and other expressions are evaluated – a maximally complete and informative property that represents the universe as being a certain way – i.e., ‘a way the world might be’.

On this construal, what have been called ‘worlds’ are better called ‘world-states’. The actual world-state is the maximal world-representing property that is instantiated; a possible world-state is one that could have been instantiated. (Soames 2010: 52)

Some sentences, it is widely supposed, are necessarily true: they could not have failed to be true, and so, in a paraphrase widely accepted among philosophers, they are true in every possible world. Two plus three equals five, a defender of this theory will urge, is surely true in every possible world…, and the same applies to Three plus four equals seven. But if Two plus three equals five and Three plus four equals seven are both true in every possible world, the theory we have been looking at is forced to say that the meaning of each of them is the set of all possible worlds. The theory predicts, in other words, that these two sentences have the same meaning.… The same kind of objection can be launched using sentences that are necessarily false [which] too are predicted to have the same meaning, namely the empty set, the unique set that has no members. (Elbourne 2011: 51)

The problem is worse. Since propositions are also the objects of the propositional attitudes, it also turns out that whenever someone believes one necessary proposition, they believe them all, since there is only one.

So someone who believes that two plus three equals five, also believes that all vixens are vixens, because both express the universal proposition, the set of all worlds:

The problem is that the possible worlds analysis seems to have the following paradoxical consequence: if a person believes that \(P\), then if \(P\) is necessarily equivalent to \(Q\), he believes that \(Q\). (Stalnaker 1984: 72)

But this seems implausible.

Note that many attitudes distribute over conjunction: so if S knows \(P \wedge Q\), S knows \(P\) and S knows \(Q\).

Let us say say that \(Q\) is a necessary consequence of \(P\) iff every possible world in which \(P\) is also a possible world in which \(Q\).

Note that if \(Q\) is any necessary consequence of \(P\), then \(P\wedge Q\) is true in exactly the same worlds as \(P\): \(⟦P⟧ = ⟦P \wedge Q⟧\). The problem now is fairly immediate:

So now anyone who believes anything at all believes every necessary consequence of it, including every necessary truth (Soames 1987: 48–50).

Can the simple view that identifies propositions and intensions respond?

The expressions ‘that \(P\)’ and ‘that \(Q\)’ are schemas for sentential complements which denote propositions. The statement ‘\(P\) is necessarily equivalent to \(Q\)’, however, is a schema for a claim about the relation between two expressions. Hence here the letters \(P\) and \(Q\) stand in for expressions that denote things that express the proposition that \(P\). Now once this is recognized, it should be clear that it is not part of the allegedly paradoxical consequence that a person must know or believe that \(P\) is equivalent to \(Q\) whenever \(P\) is equivalent to \(Q\). When a person believes that \(P\) but fails to realize that the sentence \(P\) is equivalent to the sentence \(Q\), he may fail to realize that one of the propositions he believes is expressed by that sentence. In this case, he will still believe that \(Q\), but will not himself put it that way. And it may be misleading for others to put it that way in attributing the belief to him. (Stalnaker 1984: 72)

Maybe when \(S\) believes that \(P\), \(S\) stands in the belief relation to the proposition expressed by \(P\) expresses a truth.

If sentence \(s\) expresses … proposition \(P\), then the second proposition in question is the proposition that \(s\) expresses \(P\). In cases of ignorance of necessity and equivalence… it is the second proposition that is the object of doubt and investigation. (Stalnaker 1984: 84–85)

In effect, Stalnaker swaps the necessary proposition as the object of belief with a contingent meta-linguistic proposition. And ‘it may be a nontrivial problem to see what proposition is expressed by a given sentence’ (Stalnaker 1984: 84; see also Stalnaker 1987).

A negative-polarity item is, roughly, a word that is happiest in a negative environment. Here are some examples (Ladusaw 1980: 457):

Chrysler dealers don’t ever sell any cars anymore.

*Chrysler dealers ever sell any cars anymore.

The 6:05 hasn’t arrived yet.

*The 6:05 has arrived yet.

No student has arrived yet.

*Some student has arrived yet.

In these examples, ever, any, and yet are NPIs: they are comfortable in the negative environments – in the scope of apparently negative words like don’t, hasn’t, and no student – found in the sentences (12)–(16), but awkward in the sentences (13)–(17).

The problem is that, despite their name, NPIs are also happy in a bunch of non-negative environments too:

So it is not obvious how to characterise NPIs: it is not the presence of an overt ‘negation’ operator like not or no.

Indeed, it seems implausible that it be syntactic at all: witness these non-negative but syntactically identical cases:

It’s surprising that (some/any) money was taken;

It’s plausible that (some/*any) money was taken.

It must be something about the meaning.

Ladusaw’s answer is: those expressions which are downward entailing.

Here’s Elbourne: an expression

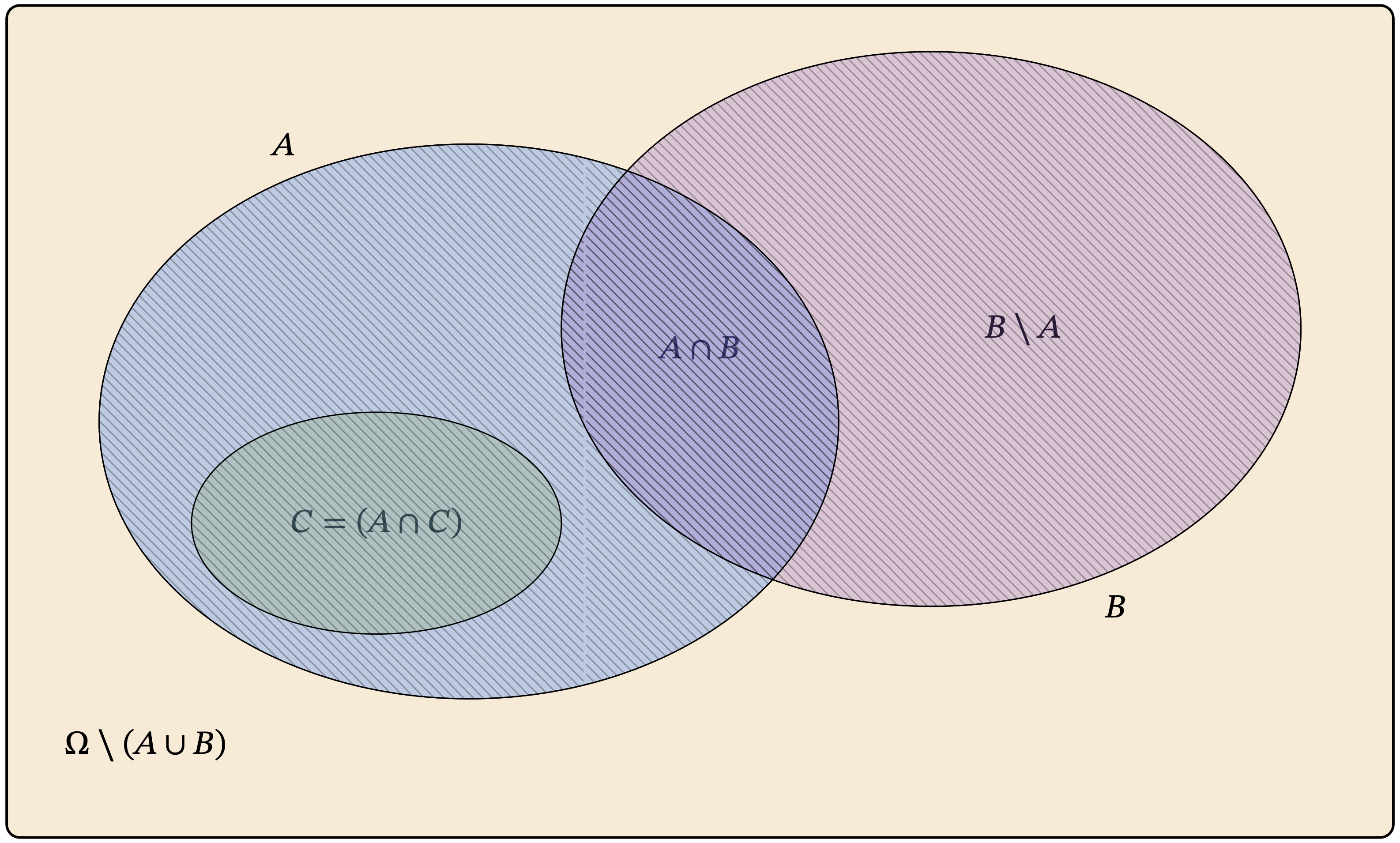

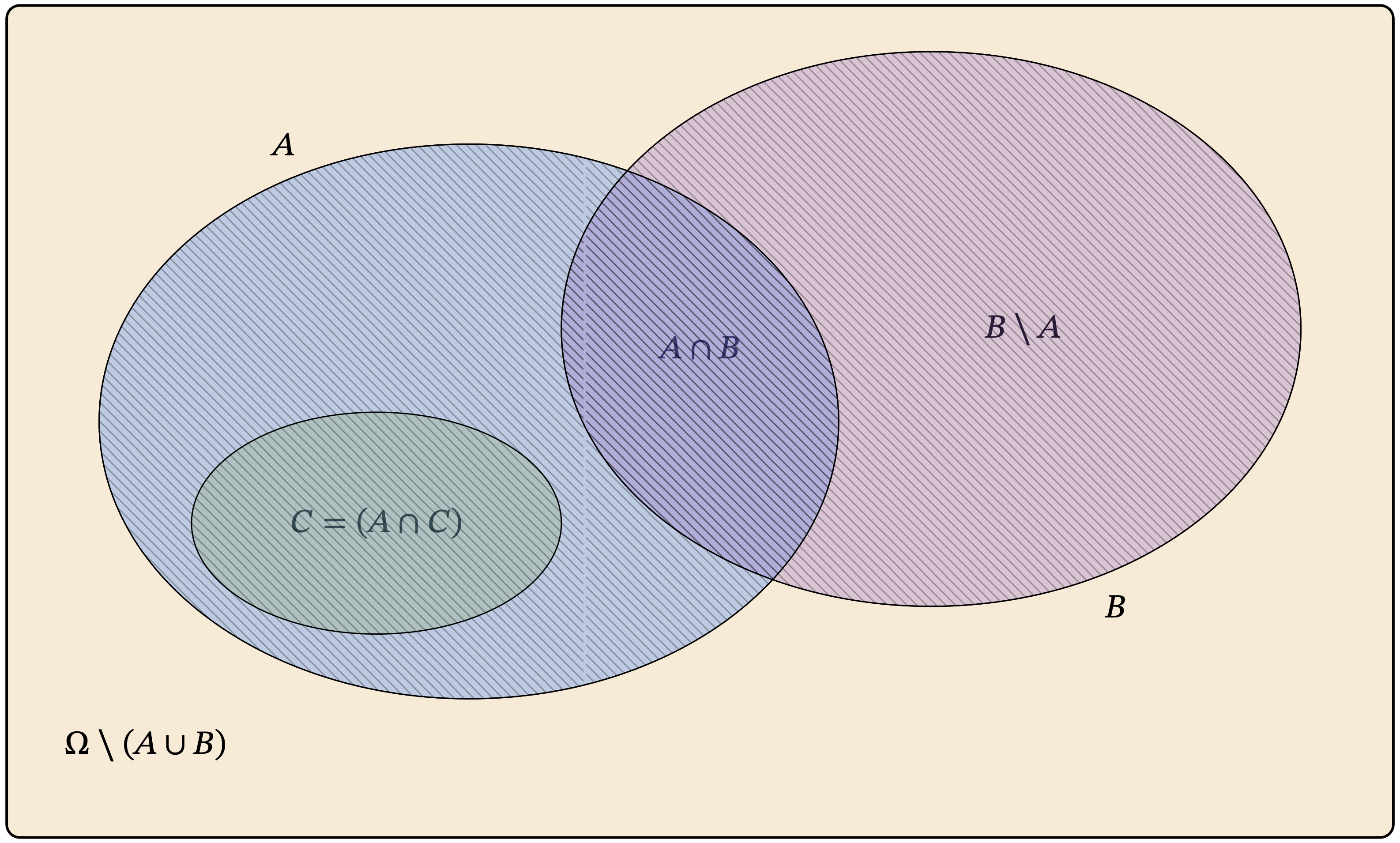

is downward entailing if and only if, for all phrases \(A\) and \(B\), if the meaning of \(B\) is a subset of the meaning of \(A\), then the sentence composed of \(O\) and \(A\) entails the sentence composed of \(O\) and \(B\). (Elbourne 2011: 58)

More formally, an expression \(O\) is downward entailing iff, for expressions \(A\) and \(B\) with sets as their intension, if \(⟦B⟧ \subseteq ⟦A⟧\), then \(⟦O(A)⟧ \subseteq ⟦O(B)⟧\) (Ladusaw 1980: 467).